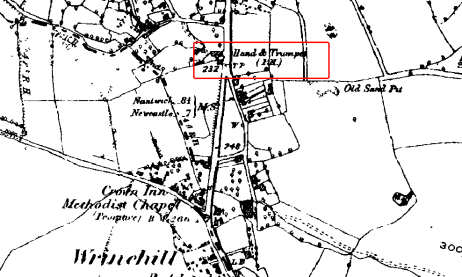

For those that don't live locally, Wrinehill is situated right next to Betley, a small market town listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 (although the market ceased trading in Victorian times). One village melds seamlessly into the other, with the Hand and Trumpet lying at the northerly edge of Wrinehill, although in archives it is often listed as being in Betley.

A map from 1891 detailing the pub

At the time of the woolly mammoth

Not many people know this, but during the last Ice Age the ice cap had its very southernmost tip at Wrinehill. The village wasn't actually there then of course, just the odd bear, but if you fast-forward some 20,000 years to 2,000 BC the locals included a Neolithic hunter-gatherer who lost his axe-hammer trudging through the forest on what is now Betley Hall estate. It was found again about 3,900 years after that, in the early 20th century.

An axehammer. Named after a local rock band

We do know there was a settlement in Betley in Saxon times, well over 1,000 years ago - a hearth place from those times was unearthed in the central area of the village near the Black Horse Inn. The name Betley is in fact of Saxon origin; the probability being that 'Beta' is a woman's name, with 'lea' meaning a clearing or glade in a wood.

By 1125 there was reportedly a chapel at Betley, and we come across the first reference to Wrinehill in 1293, although during the middle ages it was sometimes known as Wrineford, or sometimes Wrine.

Tollgates

The countryside was densely wooded in those days, with settlements in clearings with muddy tracks connecting them. The road system - or track system as it was then - has always been significant to Betley and Wrinehill. The villages lay on a route to Ireland, and apparently was renowned for raising the children left on their way by Irish women.

There was a local rhyme which referred to the ruggedness of the road:

Aidley, Madely, Keele and Castle,

Huxon, Muxon, Woore and Asson,

Rainscliffe rugged and Wrinehill's rough,

But Betley's the place where the devil came through.

In 1830 a new road was constructed in Wrinehill to avoid a steep hill, with new turnpikes at either end of the road. The earliest reference we have to the Hand and Trumpet is 1835, when Joseph Dean was the landlord, and we know that the pub was sited right next to the lower toll gate, presumably to take advantage of travellers stopping for a break and some refreshment.

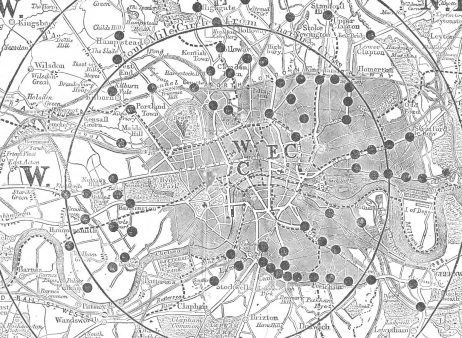

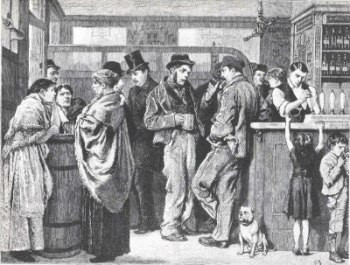

London toll pikes in 1857. Travelling

must have been endlessly frustrating

The toll system was the means by which roads were maintained and new roads built, but they were by no means popular and were frequently the cause of disturbances and riots. Turnpike Trusts or groups of businessmen owned most of the main roads in those days, and fixed the charges and decided how many tollgates, or turnpikes, could be built.

Tolls were a big expense for small farmers, who used the roads to take their crops and animals to market, and also to collect lime to improve the quality of the soil. It could cost as much as five shillings (around £20 in today's money) in tolls to move a cart of lime eight miles.

The Rebecca riots, when local farmers

broke down toll gates

The toll house is still there, but is now the double-fronted house called Hillside, on the left of the pub. In the Bluebell Inn, towards the other end of the village, there is a painted board from the Upper Tollhouse, at the other end of the toll road, which lists the charges. It is apparent that you could get a discount if your carriage or wagon had broad wheels, as these caused less damage to the road. The tolls were discontinued in 1877.

The Origin of the Name

It has intrigued us what the name "Hand and Trumpet" actually means. According to "Betley: In Old Picture Postcards" by Robert Speake, "modern visitors to the pub remember fifty years ago (i.e. in the 1930's) that men used to play cards (Pontoon) for money in the field at the back, an illegal act in those days. One of the village boys would be posted outside on the road to give warning when the policeman was in sight. The boys were paid one penny for every 'pontoon' - a good wage in those days for a boy!"

This would appear to have been the origin of the idea that the "Hand" was a hand of cards, and the "Trumpet" was the means by which the alarm was raised. There were several references to this in the painted signage of the pub when we took it over, as well as numerous decorative details within the pub itself.

However, there are a number of problems with this explanation of the origin of the name.

Firstly, this reminiscence of a gambling den stems from the 1930's, although in fact the Hand and Trumpet had already been in existence - and so named - for a hundred years or so before this.

Another difficulty with this story of the gambling den is that there were at least three other 'Hand and Trumpets' in the region - in a census of 1818 there was one in Wolverhampton, another in Radford near Stafford, and another is registered in Stone in 1829. It cannot be that all of these were illegal gambling dens, or if indeed they were, that they should wish to advertise themselves as such through their choice of name.

So where did the name come from, and what was its significance?

At that time 'the hand' was a very commonly used device in signage. Bear in mind that very few people could read and write in the early nineteenth century, so pictorial signs were hung up outside shops and businesses depicting the activity within. It was often the custom for sign painters to depict a hand emerging from clouds holding some object that depicted the business - a hand holding a coffee pot depicted a coffee house, a hand holding a pair of shears was a tailors, and so on.

The type of hand portrayed had a bearing too: a visitor to Fleet Street in the nineteenth century wrote "...et me see... where the sign is painted with a woman's hand in it, 'tis a bawdy house, where a man's it has another qualification; but where it has a star in the sign 'tis calculated for every lewd purpose."

It was common for alehouses to be named after local amenities. The Hand and Ear was next to a surgeons, as was the Hand and Face. The Hand and Flower was next to some nurseries, and the Hand and Slap was next to a cobblers (a 'slap' being a slipper). Dare I say it, but in the 1830's there was an alehouse in Whitefriars called the Hand and Cock - a pun on the name of the landlord, John Hancock.

Here are some other alehouses from the 19th Century with 'The Hand' as part of its name:

Hand and Apple (next to an orchard)

Hand and Scales (next to various trades)

Hand and Ball (next to playing fields)

Hand in Hand (Sign of Concord, or friendship)

Hand and Bible (next to a church)

Hand and Slipper (next to a cobblers)

Hand and Tench (Followers of Isaac Walton, a famous fly fisherman)

Hand and Cork (next to a vintners)

Hand and Tankard (Alehouse)

Hand and Pen (next to a scriveners)

Hand and Shears (next to the Merchant Tailors of London)

Hand and Heart (Next to a marriage Insurance office)

Hand and Tennis (adjoining a tennis court)

Hand and Hollybush (next to a church)

It is significant that the pub was right next to the tollgate. In those days, the Royal Mail coach didn't have to pay toll charges, as to stop at turnpikes would have delayed the mail. The toll-gate keeper was warned to open his gates to let mail coaches through when he heard the guard on the mail coach blowing his post-horn, or trumpet. If he failed to do so, a fine of 40 shillings was payable (about £150 in today's money). The horn also alerted innkeepers to the imminent arrival of the coach, which also carried passengers needing refreshment.

The guards on Royal Mail coaches prided themselves on their horn blowing skills - they were supplied with a three-foot long horn made of tin (nicknamed the "yard of tin"), but most bought their own made of copper or brass, giving a far better tone. The horn produced four deep and bell-like notes to produce the instantly recognisable message of "Clear the Road", which could be heard clear across the countryside.

This, we now believe, is the more likely origin of the name.

As Bill Bryson observed in Mother Tongue (1990), when considering pub names, "almost any name will do if it is at least faintly absurd, unconnected with the name of the owner, and entirely lacking in any suggestion of drinking, conversing, and enjoying oneself. At a minimum the name should puzzle foreigners -- this is a basic requirement of most British institutions -- and ideally it should excite long and inconclusive debate, defy all logical explanation, and evoke images that border on the surreal."

The Hand and Trumpet as a pub name would appear to satisfy a number of these criteria, not least of which is that it excites long and inconclusive debate.

A stagecoach approaching a tollgate

Mind you, if you do a Google search for 'Hand and Trumpet', quite a different result emerges:

"Well I've never been to heaven, but I've been told,

Hand me down my silver trumpet, Gabriel;

The gates are made of pearl, and the streets are made of gold,

Hand me down my silver trumpet, Lord."

The History of the pub

In 1851 there were eight inns in Betley and Wrinehill : the Blue Bell and the Crown at Wrinehill, the Hand and Trumpet, the Black Horse, The Swan, The Red Lion, The Lord Nelson and the Three Anchors.

One of the people who has been a lot of help in exploring the history of the pub is local historian Patrick Corness, a Betley man whose grandmother, Agnes Downend, was born at the Hand and Trumpet in 1880, when her father, Patrick's great-grandfather John Downend, was the publican. These may be Patrick's forebears in the photograph below.

This is a photograph of The Hand and Trumpet taken in about 1880. You can just make out the name on the sign. The hitching rail for horses is visible to the left of the front door. This building was at least the second building on the site, and was itself destroyed by fire in 1914 or thereabouts, when it was rebuilt in its present form.

Life in those days was harsh, and most inns had a dual purpose, either as farmhouses or places where in addition to selling ale some other industry or business was carried on. Our sister pub, the Dysart Arms in Bunbury, was simultaneously a pub and a slaughterhouse during this period.

Charles Booth, in Life and Labour of the People in London, described the life of a barman in London around 1895:

As with other servants, the hours which a barman works depend very largely upon the character of his employer; in a house which opens at 5 o'clock A.M. the hours of labour which an inhuman master exacts from his men are at times appalling, amounting in some cases to little short of sixteen on week-days and ten on Sundays; such instances are, however, rare, and the average hours of a barman are twelve to thirteen on week-days, and nine or ten on Sundays, making a week of eighty-one to eighty-eight hours. The majority of houses open at 7.30 or 8 and close at 12.30, from an hour to an hour and a half is allowed for meals, and in few cases do men have less than two hours' rest in the course of the day.

It is an invariable custom to give a holiday after 10 or 11 A.M. on one day every four weeks, and till 7 P.M. on every third Sunday, while in some cases men are allowed off from 6 to 10 o'clock on one night in each week.

The chief grievance of the barman is the very youthful age at which his chance of getting work diminishesâ?¦.masters prefer men who can give and take chaff with the customers and fear that elderly men may be too staid in their demeanourâ?¦ Unfortunately, no class of men find it harder to effect a change of calling; employers generally are said to regard unfavourably those who have been engaged in public-house work and the superannuated barman is consequently under peculiar temptation to join the great army of loafers.

Not much changes - we still look for crew who can "...give and take chaff with the customers..", and at any bar in the land you'll still hear mutterings about the "great army of loafers.." out there.

In the early part of the 20th century, the pub was run by a very well-liked man called Bache. A travelling circus called Hoginies Circus would camp in the Hand and Trumpet 'craft' (a local word meaning a small field). The circus was run by a German, but trade slipped off during the first world war when some Betley folk suspected him of being a German spy.

The Hand 'craft' where Hoginies Circus

was held. This is now the site of the pond

Significant alterations were made to the pub about twenty years ago or so. A large pond was excavated in the land to the back of the pub, and a large extension was built on the rear of the building which catered for functions and weddings, as well as having some letting bedrooms.

By the time we became involved with the pub in the summer of 2005, it had been closed down and was in a sorry state - it had been closed for some time and was damp, peeling and unloved. The pond was choked with weed and so de-oxygenated that no fish could survive, and the run-off channel that controlled the water level had collapsed.

The renovation took about six months of hard graft - we've taken the interior back to raw brick and started again. We've built a substantial deck out over the back of the pub overlooking the pond, which has also been dug out and re-lined. We've remodelled the interior so it all works in a very different way, and from the inside at least, you probably wouldn't recognise it.

It's greatly satisfying that the pub has another brand-new lease of life, and we're happy it's in good shape for the next few generations of regulars.

References:

'Betley; in old picture postcards - Robert Speake, 1984

'Betley: A village of contrasts - Robert Speake, 1980

Portrait of a Community - Mavis Smith, 1999

The Illustrated London News, June 6, 1857

William White's Gazetteer & Directory of Staffordshire 1834. 1851

Post Office Directory 1860

Piggot's Directory - Midlands 1835

History of Sign Boards, 1866 - Jacob Larwood, John Camden Hotten

Encyclopaedia of Staffordshire

Thanks to the William Salt Library, the Staffordshire Records Office, Patrick Corness and Phil Coops

Bill Bryson - Mother Tongue, 1990