The Leather Bottle dates from a time before glass was widely available, when leather was frequently used as a storage vessel for liquids. In the days when the pub first opened its doors, a leather bottle hanging outside a pub as a sign would advertise the availability of refills of ale or wine inside. This was before the majority of people could read, of course, so written signs wouldn't have been very helpful.

Leather bottles were found on Henry VIII's ship the Mary Rose, and were once common containers for wine and beer. They weren't bottle-shaped necessarily - some were a simple tube of leather with the ends stitched up leaving enough of a seam to attach a shoulder strap, others were flask-shaped, and still others were somewhat dumpy flagons. The insides were treated with black pitch to keep them waterproof, and some had beautifully embossed coverings.

Queen Anne had just died when the pub opened to serve travellers on the road from Reading to Southampton, and of course the local people. It was known as the "White Lion" in 1714 and later as "the Bottle", with Bottle Lane and Bottle Field nearby. In 1800 the landlord of the Bottle was Richard Halfacre, who kept it until 1818. By 1857 it was called the Leather Bottle when it had a landlady, Frances Berry.

Highway Robbery

The pub we see now was originally three cottages on the Reading Road which became increasingly important as a main route when it became a Toll Road. This whole area benefitted from the passing trade of coaches heading for Basingstoke, which in turn attracted Highway Robbers. Bagshot was a notorious centre for systematic robbery, and a number of colourful characters frequented the coach houses and inns in search of victims.

One such was William Davis the "Golden Farmer", who led a double life, one as a successful and respectable Corn Merchant, the other as a highwayman. He gained his moniker from his habit of only stealing gold coins: it is said he often let his victims keep their jewels and other valuables so as to avoid the possibility of his ill-gotten gains being traced. Initially operating alone, Davies became a master of disguise and, at one time, robbed his own landlord of the annual rent money just collected from him. The Golden Farmer was finally hung in chains at Tyburn in 1670.

Colonel Blood

Colonel Blood was another extraordinary local character, who almost succeeded in stealing the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London in 1671. Under the disguise of 'Parson Blood', he had befriended the keeper of the crown jewels, Talbot Edwards, and one day arrived at the Tower with his nephew and two other men under the pretence of introducing his nephew to Edwards' daughter.

While the 'nephew' was getting to know Edward's daughter, the others in the party asked if they might view the Crown Jewels. Edwards led the way downstairs and unlocked the door to the room where they were kept. At that moment Blood knocked him unconscious with a mallet and stabbed him with a sword

The grille was removed from in front of the jewels and the crown, orb and sceptre were taken out. The crown was flattened with the mallet and stuffed into a bag, and the orb stuffed down Blood's breeches. The sceptre was too long to go into the bag so Blood's brother-in-law Hunt tried to saw it in half.

At that point Edwards regained consciousness and raised the alarm. Blood and his accomplices dropped the sceptre and attempted to get away but Blood was arrested as he tried to leave the Tower by the Iron-Gate, after unsuccessfully trying to shoot one of the guards. In custody Blood refused to answer questions, instead repeating stubbornly, "I'll answer to none but the King himself".

Blood knew that the King had a reputation for liking bold scoundrels and reckoned that his considerable Irish charm would save his neck as it had done several times before in his life. Blood was taken to the Palace where he was questioned by King Charles, Prince Rupert, The Duke of York and other members of the royal family. King Charles was amused at Blood's audacity when Blood told him that the Crown Jewels were not worth the £100,000 they were valued at, but only £6,000.

The King asked Blood "What if I should give you your life?" and Blood replied humbly, "I would endeavour to deserve it, Sire!"

Blood was not only pardoned, to the disgust of Lord Ormonde, but was given Irish lands worth £500 a year. Blood became a familiar figure around London and made frequent appearances at Court

The Church at Mattingley

The Churchyard was licensed in 1425, and the first church or chapel on the present site was probably built towards the end of the l4th century. It is one of the most beautiful churches in England: it is fully half-timbered, and the bricks which are made as parallelograms and not oblongs seem to have been designed specifically for herringbone work and may well have been "burnt" on Hazeley Heath.

The Church has no patron saint - possibly because the original building on the site was, to start with, a moot hall - that is, a place where meetings were held. On the other hand it may have been because it had been, in the early days, a "chapel of ease" to the Parish Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Heckfield.

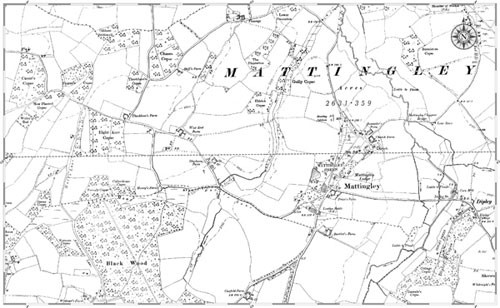

The parish of Mattingley enjoys a traditional rural way of life, the essence of which is of quietness and peacefulness. Historically, this area has always enjoyed tranquillity and has mainly been involved in farming and farming support. Manufacturing has for several hundreds of years centred around brickmaking, but this died out in the 1930s.

Stratfield Saye House

At the north end of the village can be found the main entrance to Stratfield Saye House, the home of the Dukes of Wellington, and there are several local farms belonging to the duke along with his country park and lake. South east of the London Lodges can be found the monument erected in 1866 in memory of the Duke of Wellington.

Up until the end of the 18th Century there was a fair at the end of July each year in Mattingley which attracted people from the towns around and fairground performers from across the south of England. The Parish Council meetings were held in the bar of the Leather Bottle at one time, and in Victorian times a Friendly Society met in the Inn, to which villages could regularly pay a few pence so that they could draw on the Society if they were out of work, or to pay for a decent funeral.