Roman Castlefield

To begin at the beginning, Castlefield was the site of the Roman era fort of Mamucium, established in AD 79, which guarded the Roman road that ran from Deva Victrix (Chester) to Eboracum (York). Interestingly, Mamucium means 'a hill shaped like a breast', which presumably made it easy to defend.

The fort would have been garrisoned by a cohort of about 500 troops. Originally constructed in turf and timber, it was expanded and re-inforced with stone around 200 AD, when about 1,000 men would have been stationed here. It was occupied by the Romans until AD 410 when the Romans finally left Britain to defend Rome against the Barbarians.

A Roman altar unearthed in Castlefield

(with thanks to the Greater Manchester

Archaeological Unit)

Little visible evidence survives of the Roman fort, but after extensive archaeological investigation by the Greater Manchester archaeological unit, part of the fort and the North Gate were re-constructed in 1987 together with several other noteworthy features.

The reconstructed north

gate to the fort

Castlefield and the beginning of the industrial revolution

Castlefield is a conservation area as a result of its rich industrial history: it was the terminus of the Bridgewater Canal, the world's first industrial canal built in 1764, with the oldest canal warehouse being built here in 1779.

A map of Bridgewater's canal

(with thanks to www.canalarchive.org.uk)

Some believe the building of the Bridgewater Canal marked the beginning of the industrial revolution. It was constructed to bring the Duke of Bridgewater's coal from his mine at Worsley, enabling large quantities of coal to be transported to fuel the burgeoning industries of Manchester, and enabling goods to be transported efficiently to rapidly expanding towns and cities of the north.

The project nearly bankrupted the Duke, and he had to borrow to pay his workmen. In 1765 he obtained a loan of £25,000 from Child's bank, but this was only the beginning by today's values he was eventually some £2 million or more in personal debt, but the eventual huge success of the venture ensured his fortunes were restored in the later years of his life: his annual income was said to exceed £80,000 a year in the money of the day, and he became the richest noble in England.

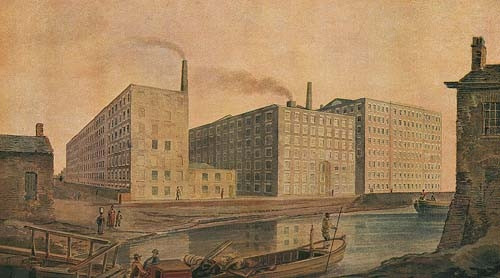

Manchester's cotton mills in 1820,

the height of the industrial revolution

Castlefield was designated as a Conservation Area in 1980 and the United Kingdom's first designated Urban Heritage Park in 1982 as part of the drive to regenerate the area.

The building

The Wharf is actually a modern building, built in 1998, but a map of the site from 1889 apparently shows two travelling cranes running on 25 foot high gantries. The wharf was open to the skies to enable the stacking of goods beside the canal.

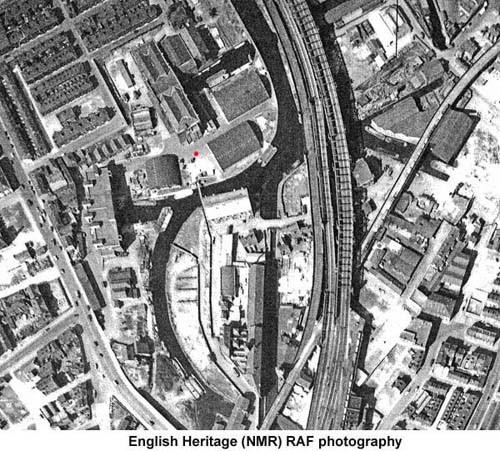

In the aerial photograph below, which comes from Manchester history website "Our Manchester" (http://manchesterhistory.net/manchester/tours/tour1/area1page63.html) the site of the Wharf has been marked with a red dot. The photograph was taken in 1953, and on the site at that time were two large Nissan-hut like commercial buildings.

An aerial view of the site

of the Wharf in 1952

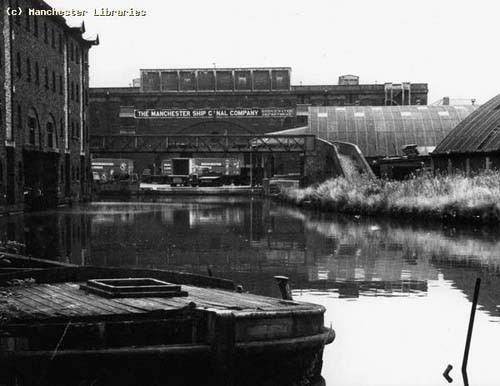

The buildings were still there when this photograph was taken in 1972:

The site of the Wharf in 1972 (with

thanks to http://images.manchester.gov.uk)

Planning battles

The building is actually a purpose-built pub which opened in 1998, when it was named Jackson's Wharf, but reviews were generally not favourable and it ceased trading in 2005. Peel Holdings, the developers of the Trafford Centre and Media City, acquired the site and attempted to develop a huge apartment block complex on the site. The original planning application was submitted in 2006.

An extract from the

Pride of Manchester's on-line

thanks to www.prideofmanchester.com)

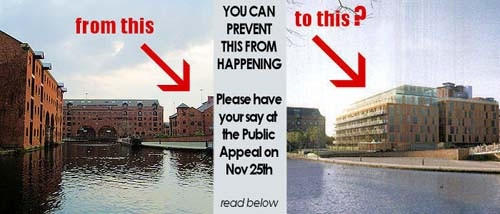

The first proposal, from the Ian Simpson practice, was for an eight-storey rectangular block, but it attracted a great deal of negative feedback because of the excessive size of the building, its incongruous appearance and the negative affect it would have on the area's application for World Heritage Site recognition. Protests were organised, and the Pride of Manchester group helped to co-ordinate opposition to the plans, enlisting the support of Mike Harding, Jason Orange of Take That, and Olympic swimmer James Hickman amongst others.

Local residents protesting about

the planning proposals (with thanks

to www.manchesterconfidential.co.uk)

Peel Holding's proposals were rejected again in 2008 by the Council's Planning Committee.

Simpson and Peel Holdings came back with a further design that involved a similar building in the form of two separate rectangular blocks. It too was rejected by the Planning Committee. Peel Holdings decided to take legal action to push the controversial plans through, which resulted in a Government appointed public enquiry.

Peel subsequently put forward a fourth proposal which also received little support, and in June 2011, after five years, Peel finally dropped their planning proposal. This was hailed by local residents and media as victory for the common man in their David and Goliath struggle with big business.

Campaigner Ian Christie, of the Castlefield Forum, said: "This is marvellous news a victory for Castlefield, common sense, conservation and everyone who wants more parks and green open space in the city." City center spokesman, Coun Pat Karney, added: "In this historic and much-loved area of Manchester, this is a victory for local residents and councillors and a victory for Manchester."

Having made an earlier approach with an offer to Peel Holdings, we recommenced negotiations to buy the building, and the transaction was completed on December 1st 2011.